Albert Camus

Man Is The Only Creature Who Refuses To Be What He Is

Always go too far, because that’s where you’ll find the truth

Albert Camus - An Overview

Albert Camus (1913–1960) was a French-Algerian born writer, political essayist and activist and, despite his protestations, a philosopher. He died in a car accident in January, 1960, at the age of 46.

His works include “The Stranger”, “The Plague”, “The Myth of Sisyphus”, “The Fall”, and “The Rebel”. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in1957, at aged 44, making him the second-youngest recipient in history.

“He ignored or opposed systematic philosophy, had little faith in rationalism, asserted rather than argued many of his main ideas, presented others in metaphors, was preoccupied with immediate and personal experience, and brooded over such questions as the meaning of life in the face of death.” [Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy]

Philosophically, Camus's views contributed to the rise of the philosophy known as absurdism, a movement which grew in response to the rise of nihilism. He is also considered to be an existentialist, even though he firmly rejected the term throughout his lifetime.

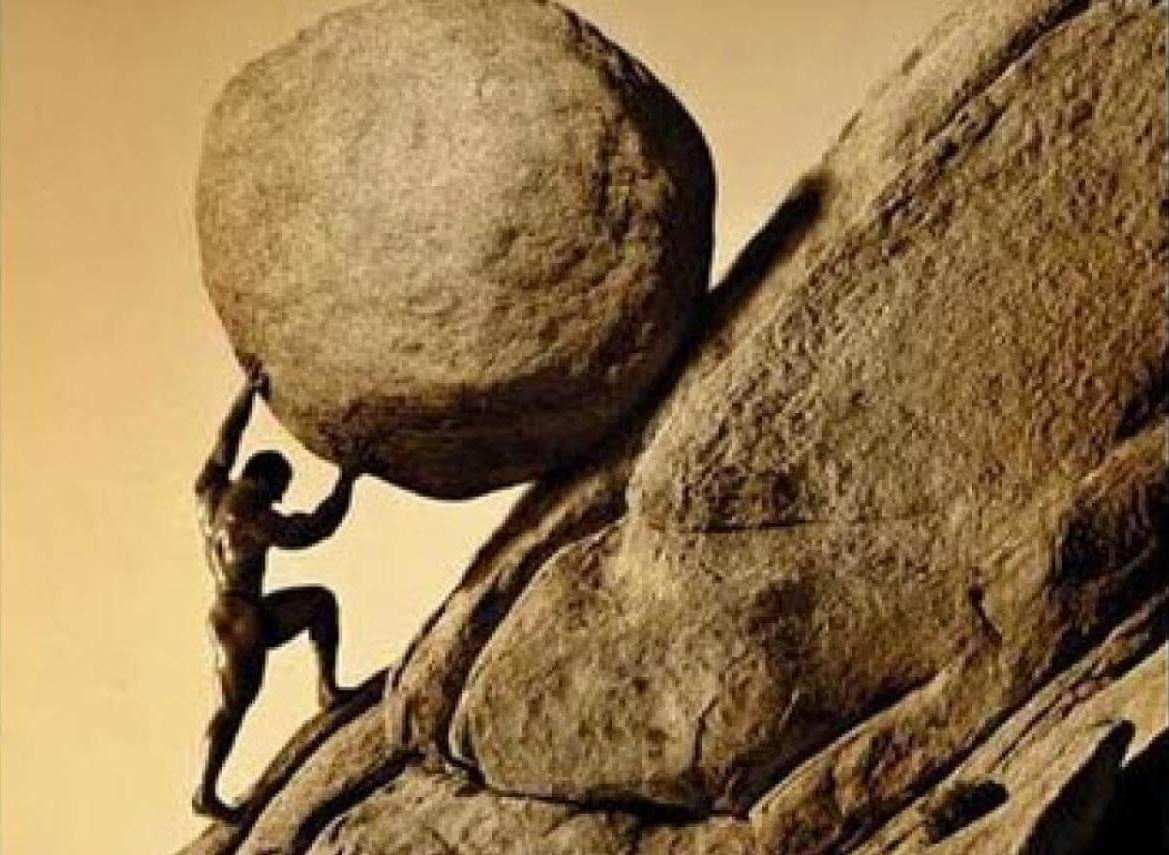

His philosophy of the absurd has left us with a striking image of the human fate: Sisyphus endlessly pushing his rock up the mountain only to see it roll back down each time he gains the top.

“The Myth of Sisyphus” was written specifically against existentialists who all assent to the absurdity of the human condition as one of their fundamental core beliefs.

Albert Camus - Sartre and Existentialism

In an interview in Les Nouvelles Littéraires, 15 November, 1945, Camus said point-blank: “I am not an existentialist.” He went on to say:

“Sartre and I are always surprised to see our names linked. We have even thought of publishing a short statement in which the undersigned declare that they have nothing in common with each other and refuse to be held responsible for the debts they might respectively incur. It’s a joke actually. Sartre and I published our books without exception before we had ever met. When we did get to know each other, it was to realize how much we differed. Sartre is an existentialist, and the only book of ideas that I have published, The Myth of Sisyphus, was directed against the so-called existentialist philosophers.”

It might be argued that Sartre and Camus are really quite similar, and that the core futility of Sartre’s philosophy parallels the despair Camus describes.

For Sartre, absurdity is obviously a fundamental condition of existence itself, frustrating us but not restricting our understanding.

For Camus, on the other hand, absurdity is not a property of existence as such, but is an essential feature of our relationship with the world.

However, Camus views the world as irrational, which means that it is not understandable through reason.

Existentialism as “philosophical suicide”

He compared existentialism to “philosophical suicide,” causing followers to make a quasi religion out of the despair and angst that crushes them.

According to Albert Camus, each existentialist writer betrayed his initial insight by seeking to appeal to something beyond the limits of the human condition, by turning to the transcendent.

And yet even if we avoid what Camus describes as such escapist efforts and continue to live without irrational appeals, the desire to do so is built into our consciousness and thus our humanity.

Put bluntly we are hardwired for transcendence.

"The Absurd is lucid reason noting its limits"

We

are unable to free ourselves from what Albert Camus refers as “this desire for unity, this longing to

solve, this need for clarity and cohesion” .

The power of acceptance

He counsels us not to give in to these impulses but rather to accept absurdity.

Camus clearly believes that the existentialist philosophers are mistaken but does not argue against them, because he believes that “there is no Truth but merely truths” or to paraphrase; it is wise to be wary of any belief system claiming a monopoly on total truth but foolish to ignore the insights and partial truths within that system.

Camus wryly notes that each thinker’s existentialist philosophy ends up being inconsistent with its own starting point: “starting from a philosophy of the world’s lack of meaning, it ends up by finding a meaning and depth in it”.

These philosophers, he insists, refuse to accept the conclusions that follow from their own premises.

Or as noted with Sartre, it

is interesting to observe that in his last days Sartre could not live

with the consequences of his own atheist existential beliefs and he became a Christian believer and called for a priest...

Footnote:

"Blessed are the hearts that can bend; they shall never be broken."

"To be happy, we must not be too concerned with others."

"In the depth of winter, I finally learned that within me there lay an invincible summer."

[Albert Camus]

Return to: Existentialism

LATEST ARTICLES

The Kingdom Is Here, Now Awakening Is Not Later -

What contemplative traditions point to - and how progress quietly replaces presence. Across contemplative traditions, a strikingly consistent message appears: truth is not somewhere else, not in the…

What contemplative traditions point to - and how progress quietly replaces presence. Across contemplative traditions, a strikingly consistent message appears: truth is not somewhere else, not in the…Does Prayer Work? The Psychology of Prayer, Meditation and Outcomes

Reality Is A Complex System Of Countless Interactions - Including Yours. So does prayer work? The problem is that the question itself is usually framed in a way that guarantees confusion. We tend to a…

Reality Is A Complex System Of Countless Interactions - Including Yours. So does prayer work? The problem is that the question itself is usually framed in a way that guarantees confusion. We tend to a…Living in Survival Mode Without Surrendering Mental Authority

Living in Survival Mode Without Surrendering Mental Authority

Clear Thinking When You’re Just Trying to Stay Afloat. Many people today are overwhelmed because they are living in survival mode - not temporarily, but as a persistent condition of life. For many, th…

Clear Thinking When You’re Just Trying to Stay Afloat. Many people today are overwhelmed because they are living in survival mode - not temporarily, but as a persistent condition of life. For many, th…Manifestation Without Magic: A Practical Model

Manifestation without magic is not a softer or more intellectual version of popular manifestation culture. It is a different model altogether. Popular manifestation teachings tend to frame reality as…

Manifestation without magic is not a softer or more intellectual version of popular manifestation culture. It is a different model altogether. Popular manifestation teachings tend to frame reality as…Staying Committed When You Can't See Progress - The Psychology of Grit

Uncertainty Is Not The Absence Of Progress, Only The Absence Of Reassurance. One of the most destabilising experiences in modern life is not failure, but uncertainty and staying committed when you can…

Uncertainty Is Not The Absence Of Progress, Only The Absence Of Reassurance. One of the most destabilising experiences in modern life is not failure, but uncertainty and staying committed when you can…The Battle For Your Mind - How To Win Inner Freedom In A Digital Age Of Distraction

From External Events to Inner Events. We often think of “events” as things that happen out there: the traffic jam, the rude comment, the delayed email reply. But what truly shapes our experience is wh…

From External Events to Inner Events. We often think of “events” as things that happen out there: the traffic jam, the rude comment, the delayed email reply. But what truly shapes our experience is wh…How to See Your Thoughts Without Becoming the Story

A Practical Guide to Thought-Awareness. You can spend your life inside the stories of your mind without ever learning how to see your thoughts clearly and objectively. Most of the stuff we tell oursel…

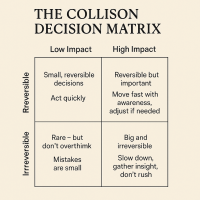

A Practical Guide to Thought-Awareness. You can spend your life inside the stories of your mind without ever learning how to see your thoughts clearly and objectively. Most of the stuff we tell oursel…The Collison Decision Matrix - A Simple Framework for Better Choices

The Collison Decision Matrix Is A Practical Everyday Thinking Tool. Most of us spend a surprising amount of time worrying about decisions. From small ones such as what to wear, what to eat, what to te…

The Collison Decision Matrix Is A Practical Everyday Thinking Tool. Most of us spend a surprising amount of time worrying about decisions. From small ones such as what to wear, what to eat, what to te…The Power Of Asking The Right Question

The Power Of Asking The Right Question Lies In The Quest For Insight. To experience the power of asking the right question you must develop the practice of asking questions. The best way to improve th…

The Power Of Asking The Right Question Lies In The Quest For Insight. To experience the power of asking the right question you must develop the practice of asking questions. The best way to improve th…Site Pathways

Here is a site pathway to help new readers of Zen-Tools navigate the material on this site. Each pathway is based around one of the many key themes covered on this site and contain a 150 word introduc…

Here is a site pathway to help new readers of Zen-Tools navigate the material on this site. Each pathway is based around one of the many key themes covered on this site and contain a 150 word introduc…How To Live With Contradiction - Beyond Thought Let Stillness Speak

A major impact on so many peoples' lives is the situational contradiction of unfilled realistic expectations. So where does all this leave us? Well here we are, with mental equipment that is more lim…

A major impact on so many peoples' lives is the situational contradiction of unfilled realistic expectations. So where does all this leave us? Well here we are, with mental equipment that is more lim…