Less Is More

Subtractive Solutions

Why Our Brains Miss Opportunities to Improve Through Subtraction

Overview: Less Is More - Subtractive Solutions

The saying "Less is more" is a phrase adopted by and attributed to architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in 1947.

But if we truly believed that less is more, why do we overdo so much?

Why do we so rarely look at a situation, object, idea or a concept that needs improving [in all contexts] and consider removing something as a solution?

Why

do our brains miss opportunities to improve through subtraction?

Why do we nearly always add something, regardless of whether it helps or

not.

A new study, featured on the cover of Nature, in which researchers at University of Virginia explain the human tendency to make change through addition, explains why.

"It happens in engineering design, which is my main interest," said Leidy Klotz, Copenhaver Associate Professor in the Department of Engineering Systems and Environment. "But it also happens in writing, cooking and everything else -- just think about your own work and you will see it"

Klotz collaborated with three colleagues from the Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy on the interdisciplinary research that shows just how additive we are by nature.

Batten public policy and psychology faculty, assistant professor Gabrielle Adams and associate professor Benjamin Converse, and former Batten postdoctoral fellow Andrew Hales, worked with Klotz on a series of observational studies and experiments to study the phenomenon.

There are two broad possibilities for why people systematically default to additive solutions:

[1] We generate ideas for both possibilities and disproportionately discard subtractive solutions, or

[2] We overlook subtractive ideas altogether

We overlook subtractive solutions because they require more effort

The research focused on the second possibility.

"Additive ideas come to mind quickly and easily, but subtractive ideas require more cognitive effort," associate professor Benjamin Converse said.

"Because people are often moving fast and working with the first ideas that come to mind, they end up accepting additive solutions without considering subtraction at all."

The researchers think there may be a self-reinforcing effect.

"The more often people rely on additive strategies, the more cognitively accessible they become," assistant professor Gabrielle Adams said.

"Over time, the habit of looking for additive ideas may get stronger and stronger, and in the long run, we end up missing out on many opportunities to improve the world by subtraction."

How to reduce your subtraction bias?

- Ask yourself “What are the things that I should avoid?” rather than asking “What should I do?”

- Ask your clients/customers what aspects of your existing services are cumbersome for them and that you could subtract?

- Rather than relying on certain technology to be more creative, identify sources of distraction, avoid interruptions and have more time to work on ideas.

- Rather than buying diet foods and pills to lose weight, eliminate specific foods for a healthier diet.

- Optimise for minimalism/less is more -in some environments this will mean decreasing the amount of time available to create a solution, in other environments this will mean increasing the time available. But the key point is optimizing for less is more.

How to use the Subtraction technique to innovate:

[This process can be adapted to different and non-commercial environments]:

- List the key components of your product or service.

- Pick one component and imagine eliminating it.

- Visualise the product or service without the key component you eliminated.

- Identify potential benefits and value of the new situation.

- If you see value in removing a component, see if you can replace the function of this component.

- Turn your idea into a valuable new product or service.

Return from "Less Is More" to: Mental Models

LATEST ARTICLES

Does Prayer Work? The Psychology of Prayer, Meditation and Outcomes

Reality Is A Complex System Of Countless Interactions - Including Yours. So does prayer work? The problem is that the question itself is usually framed in a way that guarantees confusion. We tend to a…

Reality Is A Complex System Of Countless Interactions - Including Yours. So does prayer work? The problem is that the question itself is usually framed in a way that guarantees confusion. We tend to a…Living in Survival Mode Without Surrendering Mental Authority

Living in Survival Mode Without Surrendering Mental Authority

Clear Thinking When You’re Just Trying to Stay Afloat. Many people today are overwhelmed because they are living in survival mode - not temporarily, but as a persistent condition of life. For many, th…

Clear Thinking When You’re Just Trying to Stay Afloat. Many people today are overwhelmed because they are living in survival mode - not temporarily, but as a persistent condition of life. For many, th…Manifestation Without Magic: A Practical Model

Manifestation without magic is not a softer or more intellectual version of popular manifestation culture. It is a different model altogether. Popular manifestation teachings tend to frame reality as…

Manifestation without magic is not a softer or more intellectual version of popular manifestation culture. It is a different model altogether. Popular manifestation teachings tend to frame reality as…Staying Committed When You Can't See Progress - The Psychology of Grit

Uncertainty Is Not The Absence Of Progress, Only The Absence Of Reassurance. One of the most destabilising experiences in modern life is not failure, but uncertainty and staying committed when you can…

Uncertainty Is Not The Absence Of Progress, Only The Absence Of Reassurance. One of the most destabilising experiences in modern life is not failure, but uncertainty and staying committed when you can…The Battle For Your Mind - How To Win Inner Freedom In A Digital Age Of Distraction

From External Events to Inner Events. We often think of “events” as things that happen out there: the traffic jam, the rude comment, the delayed email reply. But what truly shapes our experience is wh…

From External Events to Inner Events. We often think of “events” as things that happen out there: the traffic jam, the rude comment, the delayed email reply. But what truly shapes our experience is wh…How to See Your Thoughts Without Becoming the Story

A Practical Guide to Thought-Awareness. You can spend your life inside the stories of your mind without ever learning how to see your thoughts clearly and objectively. Most of the stuff we tell oursel…

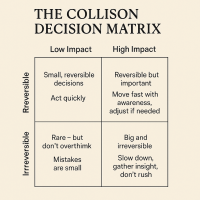

A Practical Guide to Thought-Awareness. You can spend your life inside the stories of your mind without ever learning how to see your thoughts clearly and objectively. Most of the stuff we tell oursel…The Collison Decision Matrix - A Simple Framework for Better Choices

The Collison Decision Matrix Is A Practical Everyday Thinking Tool. Most of us spend a surprising amount of time worrying about decisions. From small ones such as what to wear, what to eat, what to te…

The Collison Decision Matrix Is A Practical Everyday Thinking Tool. Most of us spend a surprising amount of time worrying about decisions. From small ones such as what to wear, what to eat, what to te…The Power Of Asking The Right Question

The Power Of Asking The Right Question Lies In The Quest For Insight. To experience the power of asking the right question you must develop the practice of asking questions. The best way to improve th…

The Power Of Asking The Right Question Lies In The Quest For Insight. To experience the power of asking the right question you must develop the practice of asking questions. The best way to improve th…Site Pathways

Here is a site pathway to help new readers of Zen-Tools navigate the material on this site. Each pathway is based around one of the many key themes covered on this site and contain a 150 word introduc…

Here is a site pathway to help new readers of Zen-Tools navigate the material on this site. Each pathway is based around one of the many key themes covered on this site and contain a 150 word introduc…How To Live With Contradiction - Beyond Thought Let Stillness Speak

A major impact on so many peoples' lives is the situational contradiction of unfilled realistic expectations. So where does all this leave us? Well here we are, with mental equipment that is more lim…

A major impact on so many peoples' lives is the situational contradiction of unfilled realistic expectations. So where does all this leave us? Well here we are, with mental equipment that is more lim…How To Trust The Process Of Mindfulness - Right Now

In mindfulness, the process isn’t some distant goal — it's what is happening right now. When we talk about how to trust the process of mindfulness the credibility of the process is heavily dependent…

In mindfulness, the process isn’t some distant goal — it's what is happening right now. When we talk about how to trust the process of mindfulness the credibility of the process is heavily dependent…