Stanford Prison Experiment

A Masterclass In Self Deception

Yes You Can Fool Most Of The People For Over 30 Years

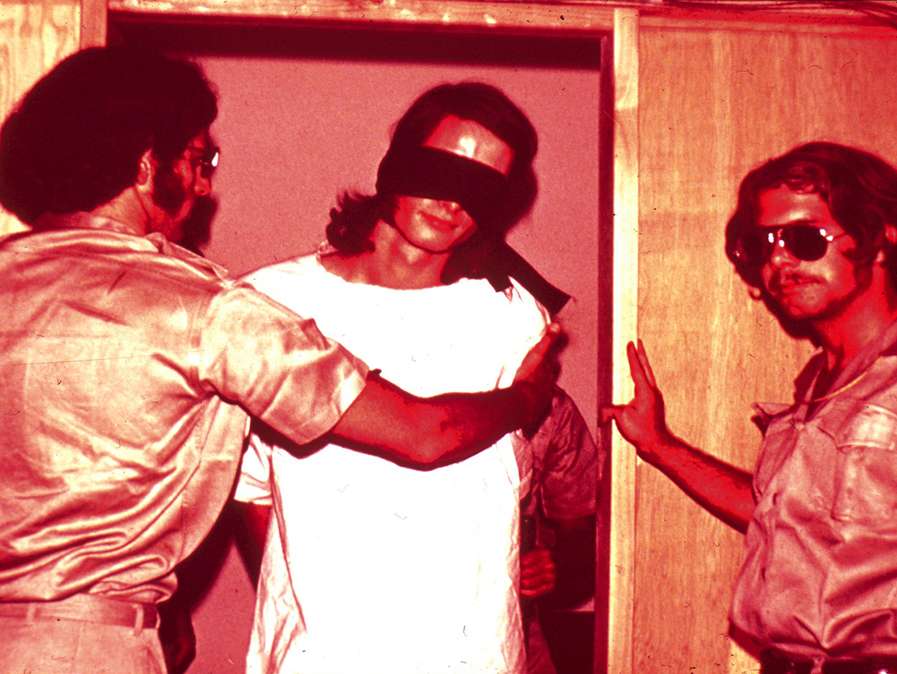

The set up of the Stanford Prison Experiment is well known as is the

outcome and the conclusions for which this study is so well known and

it has been made into a movie.

Stanford Prison Experiment - The Traditional Presentation Of Its Significance

According to Zimbardo this is evidenced by how the students who were fulfilling the role of prison guards - and thus put in a position of relative power over their prisoners - turned into monsters and abused the students playing the role of prisoners.

Things got so out of hand that the 14 day experiment had to be cut short and was terminated after 6 days because the "guards" quickly became sadistic and the "prisoners" broke down.

- The results of this study have been extensively used many times by Zimbardo and others over the past 50 years as a validation of the situational perspective of how good people are transformed into perpetrators of evil.

- This study has been used as an explanation of the prisoner torture and abuse at Abu Ghraib prison, in Iraq, in 2003 that was perpetrated by US army personnel.

Philip Zimbardo appeared as expert witness for one of the accused soldiers, Ivan "Chip" Frederick, who was subsequently found guilty and received an 8 year prison sentence.

The thrust of Zimbardo's expert testimony was that Frederick's behaviour was the result of:

- The appalling situational dynamics created by a service-man working in an environment for which he was not trained, who was grossly overworked and under supported in extremely difficult and dangerous conditions.

- The ethos of the post 9/11 "War on Terror" with the approval and enactment of the 2006 Military Commissions Act, permitting controversial practices expediting the interrogation and

prosecution of terror suspects and in effect permiting the torture and abuse of suspects.

- The rhetoric about the "War On Terror" from then President George Bush junior and Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld.

The Official Line - The "Bad Apple Theory"

The official line espoused by Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld laid the blame for the atrocities at Abu Ghraib on a few "bad

apples." This is the standard official response of deflecting any responsibility or blame away from the political and military leaders and the system they created and supported and placing the blame unfairly and squarely on the shoulders iof the service people at the bottom of the heap.

Zimbardo's Response - It's The "Bad Barrel" and The "Bad Barrel Maker"

In counterpoint to this line Zimbardo pointed to the corruption of ordinary people within the context of powerful situational forces brought about and implicitly condoned by the political and military leaders who through their policies caused and allowed the situation to happen.

Zimbardo reframed this situation as the "bad barrel", and the political and military leaders as the "bad barrel maker".

Recommended Further Reading:

The Use Of Stanford Prison Experiment Data To Enable Navy PsychOps To Break Terror Suspects

Before we get into reviewing the criticisms of the Stanford Prison Experiment it is worth noting that this study was funded by the US navy who had first access to all of the study data and who later used the material for PsyOps in prisoner interrogation...

This is a noteworthy fact as the relationship between psychology and the security state is an ambiguous relationship to put it mildly.

See: The Complicity of Psychology in the Security State

This symbiotic relationship between Zimbardo and the Navy may go some considerable way to explaining why he was so keen to create a study that proved what he wanted it to, and to declare it's findings and conclusions prior to undertaking and publishing structured analysis and receiving peer review.

Zimbardo and other psychologist and professionals from muiltple related disciplines have had, and continue to have, ongoing relationship with the Navy and Homeland security.

See: https://www.chds.us/coursefiles/press/cipert.html

The links between the Stanford Prison Experiment and Abu Ghraib are not direct as a causation of the PsychOps involvement in Abu Ghraib, nevertheless they are distinctly co-relational.

Review Of Criticisms Of The Stanford Prison Experiment

There is an overwhelming large amount of material now in the public

domain in the form of published articles and commentary on new and more

extensive data that became available c20 years ago, and referencing

in-depth professional reviews that challenge the accepted presentation

of the validity of the study.

Here is a cross-section of some of this material. I would particulaarly draw your attention to the evaluation and criticisms detailed in the review by the American Psychologiical Assocation and the response and rebuttal by Philip Zimbardo.

I have included a summary of key points from the text of each article.

ARTICLES

Inside the twisted experiment that turned students into evil sadists

He was out to answer one of the basest questions about human nature: Are we inherently good or evil? Does everyone, no matter how rich, educated or privileged, harbor a boundless capacity for sadism?

If so, can the uneven power structure of a given institution awaken a monster?

Zimbardo knew that this experiment could be a career-maker.

“I think Zimbardo wanted to create a dramatic crescendo, and then end it as quickly as possible,” prison guard John Mark told Stanford Magazine.

“He knew what he wanted and then tried to shape the experiment — by how it was constructed, and how it played out — to fit the conclusion that he had already worked out. He wanted to be able to say that college students, people from middle-class backgrounds — people will turn on each other just because they’re given a role and given power . . . I think that was a real stretch.”

And then there was Zimbardo’s prison expert, the SPE’s chief consultant Carlo Prescott, who in 2005 described himself in the Stanford Daily as “an African-American ex-con who served 17 years in San Quentin for attempted murder.” Zimbardo mined him for information.

Prescott wrote that all of the abuses perpetrated by the guards were his ideas, based on his time at San Quentin: “To allege that all these carefully tested, psychologically solid, upper-middle-class Caucasian ‘guards’ dreamed this up on their own is absurd.”

Even before those involved with the SPE spoke out, Zimbardo was criticized by the field’s most prominent thinkers. In 1973, famed German psychologist Erich Fromm tore the experiment apart.

In his book “The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness”, Fromm wrote that the SPE was contaminated from the beginning: The “prisoners” were arrested by real officers; they were made to wear clothing unlike any true inmates; the volunteers were self-selecting, and all of one class and race (save one Asian participant); most guards did not abuse the prisoners, and in fact some displayed acts of kindness.

Most crucially, all were aware they were in a mock prison, and were unduly subjected to “overt demand characteristics” — knowing what was expected of them and playing to those very expectations.

It was late in the evening of August 16th, 1971, and twenty-two-year-old Douglas Korpi, a slim, short-statured Berkeley graduate with a mop of pale, shaggy hair, was locked in a dark closet in the basement of the Stanford psychology department, naked beneath a thin white smock bearing the number 8612, screaming his head off.

“I mean, Jesus Christ, I’m burning up inside!” he yelled, kicking furiously at the door. “Don’t you know? I want to get out! This is all fucked up inside! I can’t stand another night! I just can’t take it anymore!”

It was a defining moment in what has become perhaps the best-known psychology study of all time. Whether you learned about Philip Zimbardo’s famous “Stanford Prison Experiment” in an introductory psych class or just absorbed it from the cultural ether, you’ve probably heard the basic story.

There’s just one problem: Korpi’s breakdown was a sham.

“Anybody who is a clinician would know that I was faking,” he told me last summer, in the first extensive interview he has granted in years. “If you listen to the tape, it’s not subtle. I’m not that good at acting. I mean, I think I do a fairly good job, but I’m more hysterical than psychotic.”

Now a forensic psychologist himself, Korpi told me his dramatic performance in the SPE was indeed inspired by fear, but not of abusive guards. Instead, he was worried about failing to get into grad school.

“The reason I took the job was that I thought I’d have every day to sit around by myself and study for my GREs,” Korpi explained of the Graduate Record Exams often used to determine admissions, adding that he was scheduled to take the test just after the study concluded.

Shortly after the experiment began, he asked for his study books. The prison staff refused.

The next day Korpi asked again. No dice. At that point he decided there was, as he put it to me, “no point to this job.”

First, Korpi tried faking a stomach-ache. When that didn’t work, he tried faking a breakdown.

Far from feeling traumatized, he added, he had actually enjoyed himself for much of his short tenure in the jail, other than a tussle with the guards over his bed.

Famed Stanford Prison Experiment was a fraud, scientist says

Not only was the Stanford Prison Experiment a sham, but it’s mastermind,

Stanford psychology professor Philip Zimbardo, pushed participants

towards the results he wanted...

Blum’s expose — based on previously unpublished recordings of Zimbardo, a Stanford psychology professor, and interviews with the participants — offers evidence that the “guards” were coached to be cruel.

One of the men who acted as an inmate told Blum he enjoyed the experiment because he knew the guards couldn’t actually hurt him.

“There were no repercussions. We knew [the guards] couldn’t hurt us, they couldn’t hit us. They were white college kids just like us, so it was a very safe situation,” said Douglas Korpi, who was 22-years-old when he acted as an inmate in the study.

The Real Lesson of the Stanford Prison Experiment

Taken together, these two studies don’t suggest that we all have an

innate capacity for tyranny or victimhood. Instead, they suggest that

our behavior largely conforms to our preconceived expectations. All else

being equal, we act as we think we’re expected to act—especially if

that expectation comes from above. Suggest, as the Stanford setup did,

that we should behave in stereotypical tough-guard fashion, and we

strive to fit that role. Tell us, as the BBC experimenters did, that we

shouldn’t give up hope of social mobility, and we act accordingly.

The lesson of Stanford isn’t that any random human being is capable of

descending into sadism and tyranny. It’s that certain institutions and

environments demand those behaviors—and, perhaps, can change them.

The Stanford Prison Experiment was massively influential. We just learned it was a fraud.

The Stanford Prison Experiment has been included in many, many introductory psychology textbooks and is often cited uncritically. It’s the subject of movies, documentaries, books, television shows, and congressional testimony.

But its findings were wrong. Very wrong. And not just due to its questionable ethics or lack of concrete data — but because of deceit.

Psychology has changed tremendously over the past few years. Many

studies used to teach the next generation of psychologists have been

intensely scrutinized, and found to be in error. But troublingly, the textbooks have not been updated accordingly.

The Stanford Prison Experiment is based on lies. Hear them for yourself.

Audio recording and interviews with those involved reveal the guards were coached into being mean or considered the experiment to be an “improv exercise.” Here is one of those recordings, via the Stanford archive. It’s pretty damning. You can hear David Jaffe, one of Zimbardo’s students who acted as the prison “warden,” chastising a guard for not being severe enough.

(The quality of the audio is not great. It is, after all, a nearly 50-year-old tape cassette recording. You can read the transcript below. Emphasis added.)

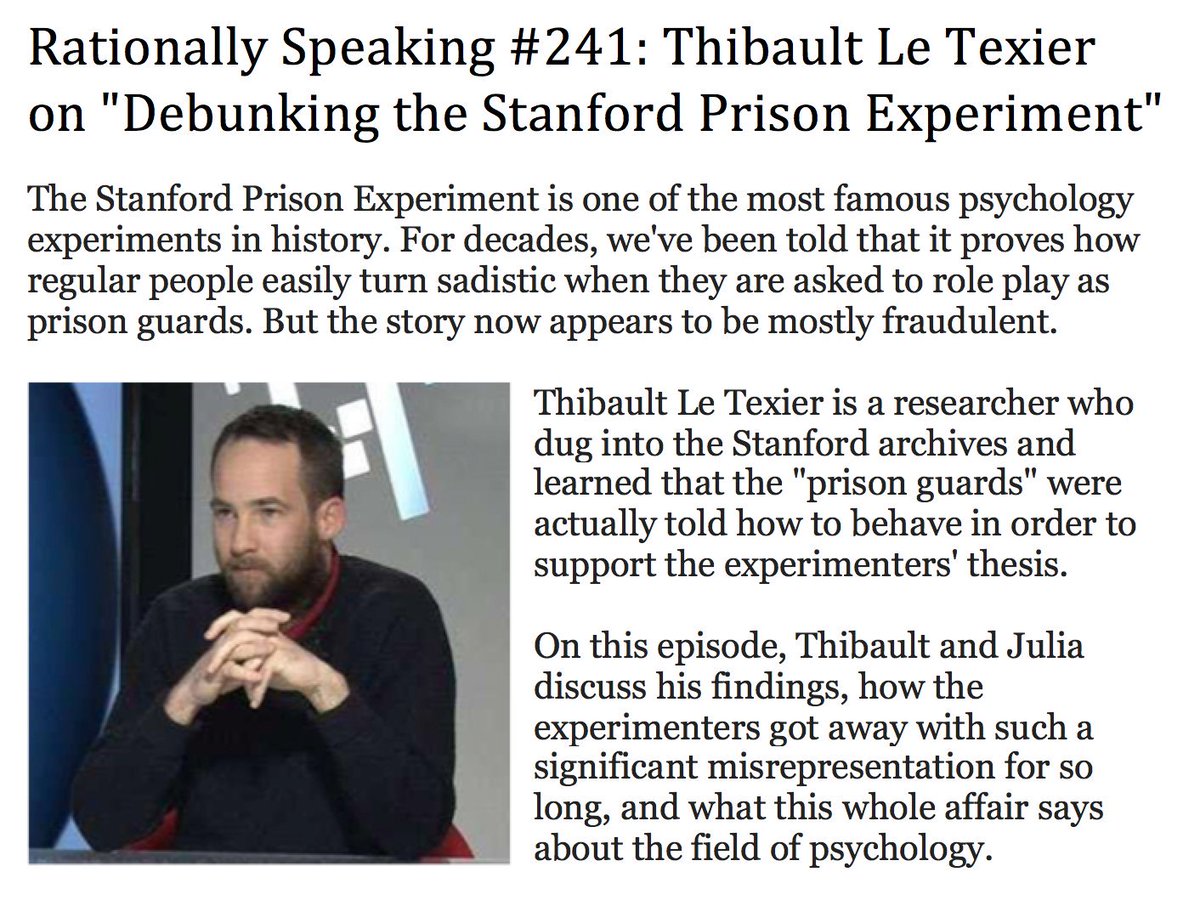

American Psychological Association - Debunking the Stanford Prison Experiment

I thoroughly recommend you download and read this professional critique.

Here is the abstract:

Thibault Le Texier

Université de Nice Sophia Antipolis

The Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE) is one of psychology’s most famous studies.

It

has been criticized on many grounds, and yet a majority of textbook

authors have ignored these criticisms in their discussions of the SPE,

thereby misleading both students and the general public about the

study’s questionable scientific validity.

Data collected from a

thorough investigation of the SPE archives and interviews with 15 of the

participants in the experiment further question the study’s scientific

merit.

These data are not only supportive of previous criticisms of the SPE, such as the presence of demand characteristics, but provide new criticisms of the SPE based on heretofore unknown information. These new criticisms include:

- the biased and incomplete collection of data,

- the extent to which the SPE drew on a prison experiment devised and conducted by students in one of Zimbardo’s classes 3 months earlier,

- the fact that the guards received precise instructions regarding the treatment of the prisoners,

- the fact that the guards were not told they were subjects,

- the fact that participants were almost never completely immersed by the situation.

Possible

explanations of the inaccurate textbook portrayal and general

misperception of the SPE’s scientific validity over the past 5 decades,

in spite of its flaws and shortcomings, are discussed.

For a counter-view, I recommend you read Zimbardo's in depth response to the key points of the various criticisms of his study.

Further reading on this site, linked articles:

LATEST ARTICLES

Manifestation Without Magic: A Practical Model

Manifestation without magic is not a softer or more intellectual version of popular manifestation culture. It is a different model altogether. Popular manifestation teachings tend to frame reality as…

Manifestation without magic is not a softer or more intellectual version of popular manifestation culture. It is a different model altogether. Popular manifestation teachings tend to frame reality as…Staying Committed When You Can't See Progress - The Psychology of Grit

Uncertainty Is Not The Absence Of Progress, Only The Absence Of Reassurance. One of the most destabilising experiences in modern life is not failure, but uncertainty and staying committed when you can…

Uncertainty Is Not The Absence Of Progress, Only The Absence Of Reassurance. One of the most destabilising experiences in modern life is not failure, but uncertainty and staying committed when you can…The Battle For Your Mind - How To Win Inner Freedom In A Digital Age Of Distraction

From External Events to Inner Events. We often think of “events” as things that happen out there: the traffic jam, the rude comment, the delayed email reply. But what truly shapes our experience is wh…

From External Events to Inner Events. We often think of “events” as things that happen out there: the traffic jam, the rude comment, the delayed email reply. But what truly shapes our experience is wh…How to See Your Thoughts Without Becoming the Story

A Practical Guide to Thought-Awareness. You can spend your life inside the stories of your mind without ever learning how to see your thoughts clearly and objectively. Most of the stuff we tell oursel…

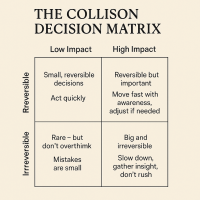

A Practical Guide to Thought-Awareness. You can spend your life inside the stories of your mind without ever learning how to see your thoughts clearly and objectively. Most of the stuff we tell oursel…The Collison Decision Matrix - A Simple Framework for Better Choices

The Collison Decision Matrix Is A Practical Everyday Thinking Tool. Most of us spend a surprising amount of time worrying about decisions. From small ones such as what to wear, what to eat, what to te…

The Collison Decision Matrix Is A Practical Everyday Thinking Tool. Most of us spend a surprising amount of time worrying about decisions. From small ones such as what to wear, what to eat, what to te…The Power Of Asking The Right Question

The Power Of Asking The Right Question Lies In The Quest For Insight. To experience the power of asking the right question you must develop the practice of asking questions. The best way to improve th…

The Power Of Asking The Right Question Lies In The Quest For Insight. To experience the power of asking the right question you must develop the practice of asking questions. The best way to improve th…Site Pathways

Here is a site pathway to help new readers of Zen-Tools navigate the material on this site. Each pathway is based around one of the many key themes covered on this site and contain a 150 word introduc…

Here is a site pathway to help new readers of Zen-Tools navigate the material on this site. Each pathway is based around one of the many key themes covered on this site and contain a 150 word introduc…How To Live With Contradiction - Beyond Thought Let Stillness Speak

A major impact on so many peoples' lives is the situational contradiction of unfilled realistic expectations. So where does all this leave us? Well here we are, with mental equipment that is more lim…

A major impact on so many peoples' lives is the situational contradiction of unfilled realistic expectations. So where does all this leave us? Well here we are, with mental equipment that is more lim…How To Trust The Process Of Mindfulness - Right Now

In mindfulness, the process isn’t some distant goal — it's what is happening right now. When we talk about how to trust the process of mindfulness the credibility of the process is heavily dependent…

In mindfulness, the process isn’t some distant goal — it's what is happening right now. When we talk about how to trust the process of mindfulness the credibility of the process is heavily dependent…Inner Mastery For Outer Impact - Mental Clarity For Effective Action

Insights only matter if they translate into consistent action. In a world crowded with quick fixes and motivational soundbites, the theme “Inner Mastery for Outer Impact” calls us to something more e…

Insights only matter if they translate into consistent action. In a world crowded with quick fixes and motivational soundbites, the theme “Inner Mastery for Outer Impact” calls us to something more e…The Wise Advocate - Helping You Achieve The Very Best Outcome

The focus of your attention in critical moments of choice either builds or restricts your capacity for achieving the best outcome. When we talk of 'The Wise Advocate' its easy to think of the consigl…

The focus of your attention in critical moments of choice either builds or restricts your capacity for achieving the best outcome. When we talk of 'The Wise Advocate' its easy to think of the consigl…Trust The Process - Beyond The Cliche

The phrase "trust the process" has become a cliche, the woo-woo mantra of the "self help" industry. Those three little words feel like they ought to mean something useful but hidden behind them are a…

The phrase "trust the process" has become a cliche, the woo-woo mantra of the "self help" industry. Those three little words feel like they ought to mean something useful but hidden behind them are a…